|

KaylieChenFirstEssay 3 - 30 May 2024 - Main.KaylieChen

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="FirstEssay" |

|---|

| | | -- By KaylieChen - 23 Feb 2024 | |

<

< | Affordable housing has long been a concern in New York and in the United States in general. But what housing conversations miss is the importance of homeownership and how BIPOC—and especially Black people—have been excluded from homeownership due to federal policies. In his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein brings up the idea of de facto vs. de jure segregation. De facto segregation is the idea that segregation is the result of private practices and not laws and is most commonly referenced when discussing the topic of segregation in neighborhoods; on the other hand, de jure segregation is segregation that is a result of law and public policy. According to Rothstein, the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which would not insure mortgages for Black people, contributed to this unconstitutional de jure segregation. The FHA would redline these communities and deem them risky to loan to. Moreover, they subsidized mass-productions of entire subdivisions but did so with a requirement that no homes be sold to Black people. Without these prohibitions, Black and white people would have been able to purchase homes at around the same rate. | >

> | Affordable housing has been a longstanding concern across the United States. However, these housing conversations often overlook the critical importance of homeownership. A study conducted by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development revealed that homeownership was an important means of wealth accumulation and was particularly important for minority and lower-income households. Despite this finding, Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC)—particularly Black communities—consistently have lower rates of homeownership when compared to their white counterparts. This is largely a result of past federal policies that systematically excluded these populations from homeownership. Through research, advocacy, and effective implementation of policies designed to promote housing affordability and eliminate discriminatory barriers, this housing inequality can begin to be addressed, and in turn, the racial wealth gap. | | | | |

<

< |

You don't need so many words on the familiar de jure/de facto distinction. This paragraph can therefore be cut by two thirds. A quote Rothsteim is all that is in addition required to support the introduction of your idea. In this draft. we are already 20% through the piece and we still don't even know what your idea is.

| >

> | Past Federal Policies | | | | |

<

< | Why Does This Matter? | >

> | In his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein highlights how the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) played a significant role in the low rates of BIPOC homeownership by refusing to insure mortgages for Black people and redlining their communities as too risky for loans. The FHA additionally subsidized the mass production of subdivisions with the stipulation that no homes be sold to Black people. These actions prevented Black people from purchasing homes at the same rate as white people, thereby creating and perpetuating racial disparities in homeownership. This practice stifled lending and investment, depressed property values, and significantly hindered economic growth in BIPOC communities. State and local governments, banks, and private developers compounded the problem with their own discriminatory practices, confining BIPOC to substandard housing and limiting their homeownership opportunities. Despite being illegal today, the legacy of these policies persists, and discrimination in housing has never fully disappeared. | | | | |

>

> |  | | | | |

<

< | Home wealth accounts for 60% of the total wealth among America’s middle class indicating that homeownership and housing appreciation are the foundations of institutional accumulation. This wealth accumulation that homeowners experience can be attributed to tax advantages and home equity. Second mortgages or home equity loans also provide a buffer against negative economic shocks. Because BIPOC were unable to purchase homes during the crucial time during the mid-1900s, they have been unable to accrue wealth at a similar rate as their white counterparts. Even if BIPOC families can purchase homes now, their homes do not grow in value as fast as whites' homes do. Homebuyers look for amenities like parks and “good schools” which are commonly found in predominantly white neighborhoods. Because of this, housing segregation can and has cost Black people tens of thousands of dollars in home equity. This inability to generate wealth causes a myriad of other problems for BIPOC, like being unable to access certain educational opportunities. For public schools, a large portion of school revenue is derived from local property taxes. Because of this government-mandated segregation, the schools BIPOC can attend generally have less funding and resources than whiter, more affluent schools. Moreover, research has shown that as the average family income in a school goes up, so too does student achievement, while schools with lower average family incomes generally feature slower learning curves. The quality of one’s education can detrimentally impact one’s future and one’s ability to be employed at a high-paying job. And, if one does not have enough money to purchase a house in a “better neighborhood,” this cycle may continue for future generations. | | | | |

<

< |

This paragraph too could be cut by 50% easily by citing Fed statistics (and in fact could be made even more tersely informative by one or two graphs produced through FRED. Where you specifically claim use research results, on the other hand, you owe the reader a link.

| >

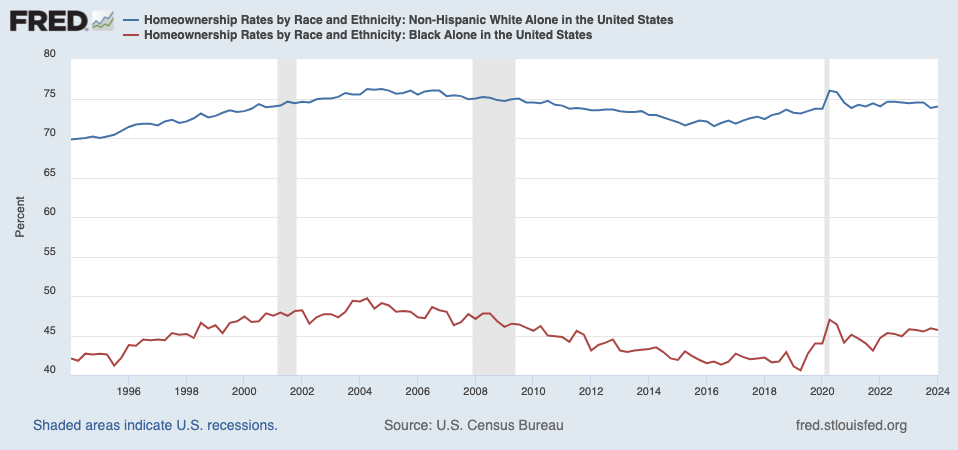

> | Figure 1: FRED graph depicting the United States homeownership rates of Non-Hispanic White and Black communities from 1994 to 2024. | | | | |

<

< |

Why Has So Little Been Done?

| | | | |

>

> | How Homeownership Leads to Wealth Accumulation | | | | |

<

< | Not everyone is aware of this history of government-mandated segregation, and if people are unaware, they do not make plans to mitigate the effects. | >

> | Thomas Shapiro, author of Race, Homeownership and Wealth, found that home wealth accounts for 60% of the total wealth among America’s middle class, indicating that homeownership and housing appreciation are the foundation of institutional accumulation. This can be attributed to several causes. According to an article by the Urban Institute, homeownership helps borrowers accumulate both housing and nonhousing wealth with tax advantages, greater financial flexibility due to secured borrowing, and built-in “default” savings with mortgage amortization and nominally fixed payments. Because BIPOC were unable to purchase homes during the crucial time in the mid-1900s, they have been unable to accrue wealth at a similar rate as their white counterparts. Even if BIPOC families purchase homes now, their homes do not grow in value as fast as whites' homes do. Homebuyers look for amenities like parks and “good schools” which are commonly found in predominantly white neighborhoods. Because of this, housing segregation can and has cost Black people tens of thousands of dollars in home equity. This inability to generate wealth causes a myriad of other problems for BIPOC, like being unable to access certain educational opportunities. For public schools, a large portion of school revenue is derived from local property taxes. As a result, the schools BIPOC can attend generally have less funding and resources than whiter, more affluent schools. Moreover, research has shown that as the average family income in a school goes up, so too does student achievement, while schools with lower average family incomes generally feature slower learning curves. Quality of education can detrimentally impact one’s future and ability to be employed at a high-paying job. And, if one does not have enough money to purchase a house in a “better neighborhood,” this cycle may continue for future generations. | | | | |

<

< |

"Not everybody" is tautological.

| >

> | What Can Be Done | | | | |

>

> | Addressing the housing affordability crisis in New York and other high-cost regions requires a multifaceted approach. Conducting research is essential to understanding the problem and exploring potential solutions. This research then allows for the education of the public and policymakers about the systemic issues contributing to the racial wealth gap and the need for targeted interventions to address these disparities. Educating the public allows impacted communities to understand their rights and the resources available to them. Grassroots organizing can also amplify the voices of those most affected by housing disparities, ensuring that their needs and perspectives are central to policy discussions. In addition to community engagement, advocacy at all levels of government is crucial in establishing policies that promote housing production and affordability while eliminating discriminatory barriers. Policymakers must first be informed about the importance of inclusive housing practices to be willing to prioritize the needs of marginalized communities. This includes supporting policies that promote economic and racial justice, even in the face of opposition from well-financed groups. Leadership that is committed to equity can drive significant change and help dismantle the systemic barriers that have perpetuated the racial wealth gap. Advocacy efforts should further extend to financial institutions to improve lending practices, ensuring that communities of color have better access to mortgages and homeownership opportunities. Effective implementation of legislation and regulations is necessary to make a real-world difference. However, it is important to remember that passing good laws is not enough; they must be enforced in a way that genuinely boosts economic security and access to housing. This requires vigilance and accountability to ensure that policies are not merely symbolic but result in actual, tangible improvements. | | | | |

<

< | Many white families, for example, are unaware of the privilege they had in being able to buy homes as a result of the FHA. | | | | |

<

< |

I doubt most US homeowners could identify FHA, explain how mortgage guarantees structure the US mortgage economy, pick Freddy and Fannie out of a lineup, or otherwise contribute to a discussion of housing finance policy. We don't run democracy under the assumption that ordinary people have the education, time or assistance necessary to understand the social complexities that they as citizens, voters, and taxpayers are ultimately responsible for.

In his book The Hidden Cost of Being African American, Thomas Shapiro found that whites hide their privilege from themselves.

A general human phenomenon, is it not? We sharpen our resentments and dull our complacencies. Christian moral thinking since Augustine has taken this as a primary theme. Behavioral economics—to take a slightly more recent form of over-simplification—also has plenty to say about it. Doubtless social policy-making involves correcting for the distortion, as politics often involves exacerbating it.

People who inherited up to hundreds of thousands of dollars from their parents insisted that they were self-reliant, unable to see how the private schools their white parents could afford to send them to, or the down payments on homes they were given, contributed to their success. There are also some who say that BIPOC can solve this issue by purchasing homes now; however, it’s not that simple. Homes in the mid-1900s were affordable to working-class families with an FHA mortgage, selling for only about twice the national median income. Today, those homes sell for six to eight times the national median income. So, although the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 allowing Black families to purchase homes, the homes were no longer affordable.

In 1968? In 1978? Would it not make some sense to provide (again, a FRED graph would be easy to make) some historical home-price information? The US is an immense country with a coherent national mortgage policy and an immense variety of local economies, land use and development legal systems, and market participants. Writing about housing policy in the US is complicated. If your intended audience is people who know about the subject, you want to make sure you acknowledge the complexities in order to maintain their trust. If you are writing for general readers, then avoiding oversimplification is part of the duty of teaching. Either way, this part of the draft needs some rethinking.

What Can We Do About This

The more people who are aware of the importance of homeownership in closing the racial wealth gap, the more likely real change can be made.

Is that true, for example, with public awareness of gender pay disparities to the reduction of those disparities? I think evidence shows that, on the contrary, public awareness that women are underpaid relative to men has steadily risen while the gap is no longer closing. But perhaps your point is more specific, and one more sentence could explain why.

To address this gap in knowledge, modifications could be made in political and social systems to include education about how government-mandated segregation occurred, and therefore, government-mandated desegregation programs should exist to counteract the problem caused by them in the first place.

Even a glancing view at contemporary cultural politics suggested that this is not a consensus suggestion. If the political will to act in this way is roughly as polarized as the political will to achieve direct intervention, why not make interventionist policy rather than education in favor of interventionist policy?

Because of a reluctance to believe that government-mandated segregation occurred, there is a hesitancy—and maybe even outright disapproval—to institute any policies to reverse its effects. Therefore, further research should be conducted to increase the amount of evidence there is that homeownership would help reduce the racial wealth gap and that lack of access to homeownership for BIPOC heavily contributed to the racial wealth gap. Moreover, understanding self-interest is the key to getting people to mobilize. If those who currently accept, and even encourage, existing power relationships had a reason to become interested and invested in affordable homeownership, it would help further this initiative. This could potentially be done by making it profitable to build affordable housing, interesting developers and their investors.

Despite the fact that the FHA was created to help families become homeowners, it excluded BIPOC, producing and reproducing privilege. Although the law is meant to bind all members of a given social community, these laws have had vastly different effects on different people, enacting inclusion in and exclusion from community membership. The law claims to be objective, but we have seen time and time again that this is not always true. The inability to accumulate generational wealth as quickly as their counterparts has led to detrimental outcomes for BIPOC, perpetuating a cycle that increases the racial wealth gap. If people are aware of how the government facilitated segregation through redlining, they can come together to change this reality that continues to plague BIPOC families today.

This is the central idea of the essay. The next draft should, as I suggested above, remodeled to put it forward from the outset, so that the reader knows what you are trying to teach. A terser and more carefully-argued middle section would then carry that idea through its development, perhaps responding to obvious objections, some of which I have tried also to put forward. Then a conclusion, in which the reader could be invited to carry the idea in a further direction, could be solidly based on the argument.

I'm not sure how persuasive that argument is, however, because I am not in general sure that in our highly-polarized period, in which the very briefest post-1965 experience with multi-racial democracy has generated such intense backlash, we can confidently expect awareness of past racial injustice to generate consensus behind remedial interventions. That does not appear to be how the Supreme Court, the Congressional Republican "majority," the MAGA coalition, or the Republican Governors Association are reading the public mood. As to the idea that public education concerning past racial discrimination can exercise comparable influence over whether people buy homes to the mortgage interest rate and the extent of household debt, I would guess that we are both in agreement that it cannot. So I am left wondering whether greater emphasis on another of your thoughts on the subject might also improve the next draft. I look forward to reading it.

| >

> | Creating a reality in which owning a home is attainable for these historically marginalized communities requires addressing the historical and ongoing injustices they face. A comprehensive approach that includes research, education, advocacy, innovative solutions, political courage, and community engagement is necessary to fulfill this vision. Through collective efforts, a more equitable society in which any resident can own a home and build wealth can slowly begin to form. | | |

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable. | | |

Note: TWiki has strict formatting rules for preference declarations. Make sure you preserve the three spaces, asterisk, and extra space at the beginning of these lines. If you wish to give access to any other users simply add them to the comma separated ALLOWTOPICVIEW list.

\ No newline at end of file | |

>

> |

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="fredgraph.png" attr="" comment="" date="1717029351" name="fredgraph.png" path="fredgraph.png" size="70781" stream="fredgraph.png" user="Main.KaylieChen" version="1" |

|---|

|

|

|

KaylieChenFirstEssay 2 - 31 Mar 2024 - Main.EbenMoglen

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="FirstEssay" |

|---|

| | | Affordable housing has long been a concern in New York and in the United States in general. But what housing conversations miss is the importance of homeownership and how BIPOC—and especially Black people—have been excluded from homeownership due to federal policies. In his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein brings up the idea of de facto vs. de jure segregation. De facto segregation is the idea that segregation is the result of private practices and not laws and is most commonly referenced when discussing the topic of segregation in neighborhoods; on the other hand, de jure segregation is segregation that is a result of law and public policy. According to Rothstein, the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which would not insure mortgages for Black people, contributed to this unconstitutional de jure segregation. The FHA would redline these communities and deem them risky to loan to. Moreover, they subsidized mass-productions of entire subdivisions but did so with a requirement that no homes be sold to Black people. Without these prohibitions, Black and white people would have been able to purchase homes at around the same rate. | |

<

< |

Why Does This Matter?

| >

> |

You don't need so many words on the familiar de jure/de facto distinction. This paragraph can therefore be cut by two thirds. A quote Rothsteim is all that is in addition required to support the introduction of your idea. In this draft. we are already 20% through the piece and we still don't even know what your idea is.

Why Does This Matter? | | |

Home wealth accounts for 60% of the total wealth among America’s middle class indicating that homeownership and housing appreciation are the foundations of institutional accumulation. This wealth accumulation that homeowners experience can be attributed to tax advantages and home equity. Second mortgages or home equity loans also provide a buffer against negative economic shocks. Because BIPOC were unable to purchase homes during the crucial time during the mid-1900s, they have been unable to accrue wealth at a similar rate as their white counterparts. Even if BIPOC families can purchase homes now, their homes do not grow in value as fast as whites' homes do. Homebuyers look for amenities like parks and “good schools” which are commonly found in predominantly white neighborhoods. Because of this, housing segregation can and has cost Black people tens of thousands of dollars in home equity. This inability to generate wealth causes a myriad of other problems for BIPOC, like being unable to access certain educational opportunities. For public schools, a large portion of school revenue is derived from local property taxes. Because of this government-mandated segregation, the schools BIPOC can attend generally have less funding and resources than whiter, more affluent schools. Moreover, research has shown that as the average family income in a school goes up, so too does student achievement, while schools with lower average family incomes generally feature slower learning curves. The quality of one’s education can detrimentally impact one’s future and one’s ability to be employed at a high-paying job. And, if one does not have enough money to purchase a house in a “better neighborhood,” this cycle may continue for future generations. | |

>

> |

This paragraph too could be cut by 50% easily by citing Fed statistics (and in fact could be made even more tersely informative by one or two graphs produced through FRED. Where you specifically claim use research results, on the other hand, you owe the reader a link.

| | |

Why Has So Little Been Done?

| |

<

< | Not everyone is aware of this history of government-mandated segregation, and if people are unaware, they do not make plans to mitigate the effects. Many white families, for example, are unaware of the privilege they had in being able to buy homes as a result of the FHA. In his book The Hidden Cost of Being African American, Thomas Shapiro found that whites hide their privilege from themselves. People who inherited up to hundreds of thousands of dollars from their parents insisted that they were self-reliant, unable to see how the private schools their white parents could afford to send them to, or the down payments on homes they were given, contributed to their success. There are also some who say that BIPOC can solve this issue by purchasing homes now; however, it’s not that simple. Homes in the mid-1900s were affordable to working-class families with an FHA mortgage, selling for only about twice the national median income. Today, those homes sell for six to eight times the national median income. So, although the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 allowing Black families to purchase homes, the homes were no longer affordable. | >

> | Not everyone is aware of this history of government-mandated segregation, and if people are unaware, they do not make plans to mitigate the effects. | | | | |

<

< |

What Can We Do About This?

| >

> |

"Not everybody" is tautological.

Many white families, for example, are unaware of the privilege they had in being able to buy homes as a result of the FHA.

I doubt most US homeowners could identify FHA, explain how mortgage guarantees structure the US mortgage economy, pick Freddy and Fannie out of a lineup, or otherwise contribute to a discussion of housing finance policy. We don't run democracy under the assumption that ordinary people have the education, time or assistance necessary to understand the social complexities that they as citizens, voters, and taxpayers are ultimately responsible for.

In his book The Hidden Cost of Being African American, Thomas Shapiro found that whites hide their privilege from themselves.

A general human phenomenon, is it not? We sharpen our resentments and dull our complacencies. Christian moral thinking since Augustine has taken this as a primary theme. Behavioral economics—to take a slightly more recent form of over-simplification—also has plenty to say about it. Doubtless social policy-making involves correcting for the distortion, as politics often involves exacerbating it.

| | | | |

<

< | The more people who are aware of the importance of homeownership in closing the racial wealth gap, the more likely real change can be made. To address this gap in knowledge, modifications could be made in political and social systems to include education about how government-mandated segregation occurred, and therefore, government-mandated desegregation programs should exist to counteract the problem caused by them in the first place. Because of a reluctance to believe that government-mandated segregation occurred, there is a hesitancy—and maybe even outright disapproval—to institute any policies to reverse its effects. Therefore, further research should be conducted to increase the amount of evidence there is that homeownership would help reduce the racial wealth gap and that lack of access to homeownership for BIPOC heavily contributed to the racial wealth gap. Moreover, understanding self-interest is the key to getting people to mobilize. If those who currently accept, and even encourage, existing power relationships had a reason to become interested and invested in affordable homeownership, it would help further this initiative. This could potentially be done by making it profitable to build affordable housing, interesting developers and their investors. | >

> | People who inherited up to hundreds of thousands of dollars from their parents insisted that they were self-reliant, unable to see how the private schools their white parents could afford to send them to, or the down payments on homes they were given, contributed to their success. There are also some who say that BIPOC can solve this issue by purchasing homes now; however, it’s not that simple. Homes in the mid-1900s were affordable to working-class families with an FHA mortgage, selling for only about twice the national median income. Today, those homes sell for six to eight times the national median income. So, although the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 allowing Black families to purchase homes, the homes were no longer affordable.

In 1968? In 1978? Would it not make some sense to provide (again, a FRED graph would be easy to make) some historical home-price information? The US is an immense country with a coherent national mortgage policy and an immense variety of local economies, land use and development legal systems, and market participants. Writing about housing policy in the US is complicated. If your intended audience is people who know about the subject, you want to make sure you acknowledge the complexities in order to maintain their trust. If you are writing for general readers, then avoiding oversimplification is part of the duty of teaching. Either way, this part of the draft needs some rethinking.

What Can We Do About This

The more people who are aware of the importance of homeownership in closing the racial wealth gap, the more likely real change can be made.

Is that true, for example, with public awareness of gender pay disparities to the reduction of those disparities? I think evidence shows that, on the contrary, public awareness that women are underpaid relative to men has steadily risen while the gap is no longer closing. But perhaps your point is more specific, and one more sentence could explain why.

To address this gap in knowledge, modifications could be made in political and social systems to include education about how government-mandated segregation occurred, and therefore, government-mandated desegregation programs should exist to counteract the problem caused by them in the first place.

Even a glancing view at contemporary cultural politics suggested that this is not a consensus suggestion. If the political will to act in this way is roughly as polarized as the political will to achieve direct intervention, why not make interventionist policy rather than education in favor of interventionist policy?

Because of a reluctance to believe that government-mandated segregation occurred, there is a hesitancy—and maybe even outright disapproval—to institute any policies to reverse its effects. Therefore, further research should be conducted to increase the amount of evidence there is that homeownership would help reduce the racial wealth gap and that lack of access to homeownership for BIPOC heavily contributed to the racial wealth gap. Moreover, understanding self-interest is the key to getting people to mobilize. If those who currently accept, and even encourage, existing power relationships had a reason to become interested and invested in affordable homeownership, it would help further this initiative. This could potentially be done by making it profitable to build affordable housing, interesting developers and their investors. | | | Despite the fact that the FHA was created to help families become homeowners, it excluded BIPOC, producing and reproducing privilege. Although the law is meant to bind all members of a given social community, these laws have had vastly different effects on different people, enacting inclusion in and exclusion from community membership. The law claims to be objective, but we have seen time and time again that this is not always true. The inability to accumulate generational wealth as quickly as their counterparts has led to detrimental outcomes for BIPOC, perpetuating a cycle that increases the racial wealth gap. If people are aware of how the government facilitated segregation through redlining, they can come together to change this reality that continues to plague BIPOC families today. | |

>

> |

This is the central idea of the essay. The next draft should, as I suggested above, remodeled to put it forward from the outset, so that the reader knows what you are trying to teach. A terser and more carefully-argued middle section would then carry that idea through its development, perhaps responding to obvious objections, some of which I have tried also to put forward. Then a conclusion, in which the reader could be invited to carry the idea in a further direction, could be solidly based on the argument.

I'm not sure how persuasive that argument is, however, because I am not in general sure that in our highly-polarized period, in which the very briefest post-1965 experience with multi-racial democracy has generated such intense backlash, we can confidently expect awareness of past racial injustice to generate consensus behind remedial interventions. That does not appear to be how the Supreme Court, the Congressional Republican "majority," the MAGA coalition, or the Republican Governors Association are reading the public mood. As to the idea that public education concerning past racial discrimination can exercise comparable influence over whether people buy homes to the mortgage interest rate and the extent of household debt, I would guess that we are both in agreement that it cannot. So I am left wondering whether greater emphasis on another of your thoughts on the subject might also improve the next draft. I look forward to reading it.

| | |

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable.

To restrict access to your paper simply delete the "#" character on the next two lines: |

|

|

KaylieChenFirstEssay 1 - 24 Feb 2024 - Main.KaylieChen

|

|

>

> |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="FirstEssay" |

|---|

Homeownership and Wealth Disparities

-- By KaylieChen - 23 Feb 2024

Affordable housing has long been a concern in New York and in the United States in general. But what housing conversations miss is the importance of homeownership and how BIPOC—and especially Black people—have been excluded from homeownership due to federal policies. In his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein brings up the idea of de facto vs. de jure segregation. De facto segregation is the idea that segregation is the result of private practices and not laws and is most commonly referenced when discussing the topic of segregation in neighborhoods; on the other hand, de jure segregation is segregation that is a result of law and public policy. According to Rothstein, the creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which would not insure mortgages for Black people, contributed to this unconstitutional de jure segregation. The FHA would redline these communities and deem them risky to loan to. Moreover, they subsidized mass-productions of entire subdivisions but did so with a requirement that no homes be sold to Black people. Without these prohibitions, Black and white people would have been able to purchase homes at around the same rate.

Why Does This Matter?

Home wealth accounts for 60% of the total wealth among America’s middle class indicating that homeownership and housing appreciation are the foundations of institutional accumulation. This wealth accumulation that homeowners experience can be attributed to tax advantages and home equity. Second mortgages or home equity loans also provide a buffer against negative economic shocks. Because BIPOC were unable to purchase homes during the crucial time during the mid-1900s, they have been unable to accrue wealth at a similar rate as their white counterparts. Even if BIPOC families can purchase homes now, their homes do not grow in value as fast as whites' homes do. Homebuyers look for amenities like parks and “good schools” which are commonly found in predominantly white neighborhoods. Because of this, housing segregation can and has cost Black people tens of thousands of dollars in home equity. This inability to generate wealth causes a myriad of other problems for BIPOC, like being unable to access certain educational opportunities. For public schools, a large portion of school revenue is derived from local property taxes. Because of this government-mandated segregation, the schools BIPOC can attend generally have less funding and resources than whiter, more affluent schools. Moreover, research has shown that as the average family income in a school goes up, so too does student achievement, while schools with lower average family incomes generally feature slower learning curves. The quality of one’s education can detrimentally impact one’s future and one’s ability to be employed at a high-paying job. And, if one does not have enough money to purchase a house in a “better neighborhood,” this cycle may continue for future generations.

Why Has So Little Been Done?

Not everyone is aware of this history of government-mandated segregation, and if people are unaware, they do not make plans to mitigate the effects. Many white families, for example, are unaware of the privilege they had in being able to buy homes as a result of the FHA. In his book The Hidden Cost of Being African American, Thomas Shapiro found that whites hide their privilege from themselves. People who inherited up to hundreds of thousands of dollars from their parents insisted that they were self-reliant, unable to see how the private schools their white parents could afford to send them to, or the down payments on homes they were given, contributed to their success. There are also some who say that BIPOC can solve this issue by purchasing homes now; however, it’s not that simple. Homes in the mid-1900s were affordable to working-class families with an FHA mortgage, selling for only about twice the national median income. Today, those homes sell for six to eight times the national median income. So, although the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 allowing Black families to purchase homes, the homes were no longer affordable.

What Can We Do About This?

The more people who are aware of the importance of homeownership in closing the racial wealth gap, the more likely real change can be made. To address this gap in knowledge, modifications could be made in political and social systems to include education about how government-mandated segregation occurred, and therefore, government-mandated desegregation programs should exist to counteract the problem caused by them in the first place. Because of a reluctance to believe that government-mandated segregation occurred, there is a hesitancy—and maybe even outright disapproval—to institute any policies to reverse its effects. Therefore, further research should be conducted to increase the amount of evidence there is that homeownership would help reduce the racial wealth gap and that lack of access to homeownership for BIPOC heavily contributed to the racial wealth gap. Moreover, understanding self-interest is the key to getting people to mobilize. If those who currently accept, and even encourage, existing power relationships had a reason to become interested and invested in affordable homeownership, it would help further this initiative. This could potentially be done by making it profitable to build affordable housing, interesting developers and their investors.

Despite the fact that the FHA was created to help families become homeowners, it excluded BIPOC, producing and reproducing privilege. Although the law is meant to bind all members of a given social community, these laws have had vastly different effects on different people, enacting inclusion in and exclusion from community membership. The law claims to be objective, but we have seen time and time again that this is not always true. The inability to accumulate generational wealth as quickly as their counterparts has led to detrimental outcomes for BIPOC, perpetuating a cycle that increases the racial wealth gap. If people are aware of how the government facilitated segregation through redlining, they can come together to change this reality that continues to plague BIPOC families today.

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable.

To restrict access to your paper simply delete the "#" character on the next two lines:

Note: TWiki has strict formatting rules for preference declarations. Make sure you preserve the three spaces, asterisk, and extra space at the beginning of these lines. If you wish to give access to any other users simply add them to the comma separated ALLOWTOPICVIEW list. |

|

|